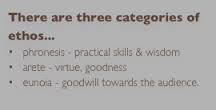

While many points of the reading this week were interesting, the new taxonomy of significant learning and the three “interest-killing approaches—the technical, the judgmental, and the documentary—” inspired the most reflective thought for me this week. I saw much overlap with works we have previously read this semester and conversations in which we have engaged. For example, Fink’s “significant learning” sounds quite similar in many ways to “learning transfer,” both as end goals for course designs and student learning. Also, many of the pieces were either implicitly or explicitly promoting a metacognitive approach to the classroom and the learning process.

I found Fink’s piece rather idealistic in his discussion of change as the absolute assessment tool for significant learning, and maybe it is the mere adjective significant that warrants such a grandiose claim as “No change, no learning.” Maybe I am just extra cynical in my fourth quarter state of exhaustion, but this maxim seems to belittle much of what we as teachers do on a daily basis. I am not naive enough to think that every single day with be life-changing for all students, and we have already discussed how the entire educational system does need an overhaul.

However, statements such as the following place a tremendous amount of pressure upon us as instructors as we strive for perfection in our course designs: “significant learning requires that there be some kind of lasting change that is important in terms of the learner’s life” (3). In some ways, I read this text and see Fink as calling for a version of the Multiliteracies’ “Transformed Practice” as the goal. That seems doable; we provide multiple contexts for learning so that students can practice adapting the knowledge and skills they are gleaning. In other ways, as I look to his concluding thoughts, his ideas seem more encompassing; anything from “application learning” to “foundational knowledge” can be significant learning, and that leaves me asking what’s so new about this taxonomy anyway?

The Morson text, on the other hand, had me nodding in agreement throughout its entirety. I kept saying, “Yes, my students need this! They have no empathy and position themselves as the victims on a daily basis!” Yet, by the end of the article, my reflection turned inward and I had to acknowledge my own tendencies to dismiss literature for any one of the three approaches mentioned: technical, judgmental, or documentary. I appreciated this reminder: “To teach anything well, you have to place yourself in the position of the learner who does not already know the basics and has to be persuaded that the subject is worth studying.” What an excellent prompt for reflective practice! I am currently teaching Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar to my sophomores. You can imagine how excited they are in April about Elizabethan drama. If I take the time at the start of each unit I teach to re-situate myself as learner alongside my students, much as Freire encourages, the students and I can dialogically seek persuasion for validity of Shakespearean studies.

There were so many points within this article that I highlighted and could expound upon reflectively; however, I leave you with just one more thought-provoking quote: “We grow wiser, and we understand ourselves better, if we can put ourselves in the position of those who think differently.” In our current culture of exaggerated differences and hostility in nearly all arenas, how great a gift we possess in literature’s capacity to allow us the chance to enter another’s shoes and to invite our students to the same right along with us. To more shoe swapping!

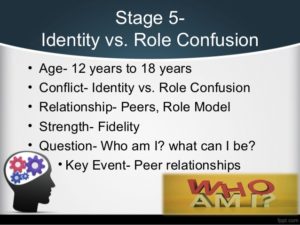

my chosen research topic of rhetoric of identity,

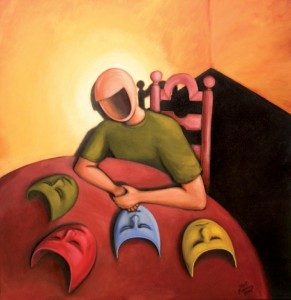

my chosen research topic of rhetoric of identity,  school was volatile in many ways as worldviews clashed around me and much was determined for me. I am grateful for many reasons for the protective environment in which I was raised and in which I now find myself as a faculty member. However, my role as teacher now affords me a different perspective on these ideological forces, and I feel a responsibility to my students to act as a catalyst for them, to expose them to ideas beyond the horizon of the tension-filled ideologies of religion and education. For in these types of institutions, much as

school was volatile in many ways as worldviews clashed around me and much was determined for me. I am grateful for many reasons for the protective environment in which I was raised and in which I now find myself as a faculty member. However, my role as teacher now affords me a different perspective on these ideological forces, and I feel a responsibility to my students to act as a catalyst for them, to expose them to ideas beyond the horizon of the tension-filled ideologies of religion and education. For in these types of institutions, much as

dedication to metacognitive reflection, rhetorical identification perhaps moreso because of the uniquely personal nature of identity research. These times of reflection should lead to a sense of ownership that moves one to civic engagement of some capacity. Ivory towers and academic silos are not where English Studies belong, much have we have discussed this semester; and any scholar of rhetoric of identity should show ownership of this move to engage the public with ideas, theories, and findings. Everyone has an innate desire to belong; identification rhetoric can provide a means for engaging this desire to be “both joined together, yet separate from” a community (Burke 1325). For me, in this phase of my life, being a scholar of rhetoric of identity means that I make myself

dedication to metacognitive reflection, rhetorical identification perhaps moreso because of the uniquely personal nature of identity research. These times of reflection should lead to a sense of ownership that moves one to civic engagement of some capacity. Ivory towers and academic silos are not where English Studies belong, much have we have discussed this semester; and any scholar of rhetoric of identity should show ownership of this move to engage the public with ideas, theories, and findings. Everyone has an innate desire to belong; identification rhetoric can provide a means for engaging this desire to be “both joined together, yet separate from” a community (Burke 1325). For me, in this phase of my life, being a scholar of rhetoric of identity means that I make myself

from which to pull objects of study.

from which to pull objects of study.

ons in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator (

ons in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator ( text,

text,

of this research, he defines rhetorical leadership “as the process of discovering, articulating, and sharing the available means of influence in order to motivate human agents in a particular situation…it is leadership exerted through talk or persuasion” (Dorsey as qtd. on 670). His method is a “line-by-line content analysis through all of the State of the Union Addresses from George Washington to George W. Bush to count elements such as word length, specific word usage, and context” (671). These categories are designed to highlight both audience in address to congress vs. the people and speaker in identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Teten concludes “that presidential rhetoric may not be easily categorized as simply ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’” (670, 671).

of this research, he defines rhetorical leadership “as the process of discovering, articulating, and sharing the available means of influence in order to motivate human agents in a particular situation…it is leadership exerted through talk or persuasion” (Dorsey as qtd. on 670). His method is a “line-by-line content analysis through all of the State of the Union Addresses from George Washington to George W. Bush to count elements such as word length, specific word usage, and context” (671). These categories are designed to highlight both audience in address to congress vs. the people and speaker in identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Teten concludes “that presidential rhetoric may not be easily categorized as simply ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’” (670, 671). Zarefsky’s

Zarefsky’s intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.