Sipiora, Phillip. “Ethical Argumentation in Darwin’s Origin of the Species.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1995, 265-292.

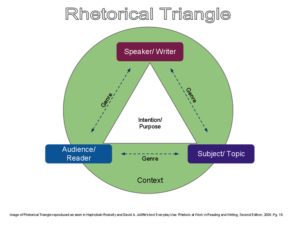

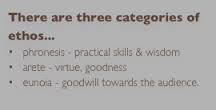

Sipiora, using a discourse analysis methodology, rhetorically analyses Darwin’s foundational  text, On the Origin of Species. Sipiora claims that this scientific discourse breaks traditions in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator (speaker) is constantly aware of and seeking to built a relationship of trust with the reader (audience). He does so using three of Aristotle’s subappeals: virtue (arete), goodwill (eunoia), and good sense (phronesis) (266).

text, On the Origin of Species. Sipiora claims that this scientific discourse breaks traditions in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator (speaker) is constantly aware of and seeking to built a relationship of trust with the reader (audience). He does so using three of Aristotle’s subappeals: virtue (arete), goodwill (eunoia), and good sense (phronesis) (266).

Virtue (arete) is found in Darwin’s passive constructions, establishment of professional integrity, patterns of self-effacement, third-person references, stative verbs, and catenative constructions. In utilizing these rhetorical devices, Darwin rests his dependence “on his attempts to involve the reader in the progressive development of the argument” (276). His “self-deprecating, self-correcting stance is a persuasive ethical strategy,” which Sipiora argues is key to his ethical argumentation (275).

Darwin’s use of goodwill (eunoia) is key in the “conjoining of rhetor and audience in a common endeavor” (276). This is accomplished through rhetorical devices such as identification rhetorical pronoun usage (we, our), rhetorical questioning, value appeals, first-person references (to highlight collective ignorance), and conditional clauses (if). Sipiora calls Darwin’s use of goodwill a “double-edged strategy…[and] a powerful rhetorical weapon…[for] simultaneous bonding with and manipulating of the reader” (279, 280).

Lastly, Darwin highlights good sense (phronesis) in his emphasis on probability. Comment clauses, integration of both first and third person pronouns (I, we), and strategic location of his argument within “accepted scientific investigation” all work together to “appeal to common sense” (282). Readers “are forced to rely on the good judgment of the expositor” because of our general lack of scientific knowledge and our ignorance exploited through these subappeals (287).

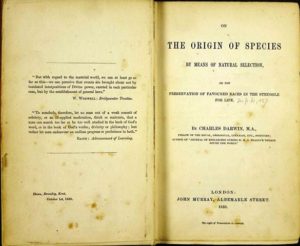

First Edition showing theological quotes by William Whewell & Francis Bacon

While Sipiora is not claiming that Darwin ignores pathos and logos, he is claiming that ethos was more important to Darwin in the writing of this text as “it is crucial that the scientific rhetor create a persona that emanates credibility” because of the time in which the book was published in 1859 (269). In fact, Darwin was so sure that the Church of the time would see the text as heretical, the first edition opened with two theological quotes to start establishing his credibility with his audience immediately. Sipiora ends by addressing the “so what” question: “Perhaps exploring the rhetoric of ethics in scientific texts will lead us to ask generative questions about ethical dimensions and implications far beyond the texts themselves” (288).

Sipiora’s multidisciplinary argument is unique in that it is analyzing a scientific text through a rhetorical lens. Typically, scientific discourse falls into the technical writing territory. Sipiora’s claim that Darwin’s text is in fact a rhetorical argument fits within the scope of Carolyn R. Miller’s claim that the positivist legacy of scientific discourse relaying Truth (uppercase implying absolute) isn’t valid. All writing is arguing for an interpretation of the world around us and is therefore arguing for truth (lowercase implying subjective). Considering Sipiora’s argument, Darwin’s text just might be proof of that claim.

I selected this article to demonstrate the rhetorical methodology of discourse analysis and because it deals with identification. In fact, Sipiora directly references Kenneth Burke’s identification: “The expositor-narrator must share some of the reader’s basic assumptions, what Kenneth Burke calls ‘identification,’ and it is this evolving identification with the reader that makes the Origin such a powerful rhetorical argument” (268). Burke’s theories of consubstantiality are of particular interest to me based on my personal course outcomes to explore major theorists and conversations surrounding rhetoric of identity.

Works Cited

Miller, C. R. “A humanistic rationale for technical writing.” College English, vol. 40, no. 6, 1979, pp. 610-617.

of this research, he defines rhetorical leadership “as the process of discovering, articulating, and sharing the available means of influence in order to motivate human agents in a particular situation…it is leadership exerted through talk or persuasion” (Dorsey as qtd. on 670). His method is a “line-by-line content analysis through all of the State of the Union Addresses from George Washington to George W. Bush to count elements such as word length, specific word usage, and context” (671). These categories are designed to highlight both audience in address to congress vs. the people and speaker in identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Teten concludes “that presidential rhetoric may not be easily categorized as simply ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’” (670, 671).

of this research, he defines rhetorical leadership “as the process of discovering, articulating, and sharing the available means of influence in order to motivate human agents in a particular situation…it is leadership exerted through talk or persuasion” (Dorsey as qtd. on 670). His method is a “line-by-line content analysis through all of the State of the Union Addresses from George Washington to George W. Bush to count elements such as word length, specific word usage, and context” (671). These categories are designed to highlight both audience in address to congress vs. the people and speaker in identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Teten concludes “that presidential rhetoric may not be easily categorized as simply ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’” (670, 671). Zarefsky’s

Zarefsky’s intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.