Jarratt, Susan C., and Nedra Reynolds. “The Splitting Image: Contemporary Feminisms and the Ethics of ethos.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1995, 37-63.

In moving away from a traditional Aristotelian sense of ethos, Jarratt and Reynolds marry sophist rhetoric and feminist theory to define ethos in a manner that recognizes difference and therefore makes a space for gender theory. Neither deconstruction nor Enlightenment era notions of the self work for feminist ethos; deconstructionism destabilizes the self in such a way that also destabilizes feminism. The Enlightenment era clings to Aristotelian notions of the self that don’t allow for difference. However, from Isocrates to Protagoras and Gorgias,  these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47).

these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47).

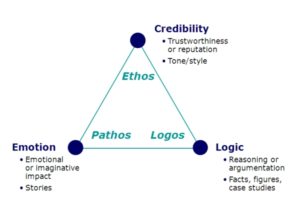

Utilizing a multidisciplinary approach that relies on feminism, rhetoric, and poststructuralism, the authors are able to “reread classical ethos through feminist history” (40). While older definitions of ethos point to customs or habits, newer notions point to character. Neither of these totally serve the purposes of feminist rhetorical goals. A rereading highlights character development through custom and habit (44). By tracing etymological definitions for key terms such as as ethea and nomos, the authors are able to locate a connection to the newer term of positionality, coined within this context by Linda Alcoff. It is precisely this “‘place from which values are interpreted and constructed rather than as a locus of an already determined set of values’” that allows a rereading of the classical notion of ethos that will acknowledge difference and therefore give voice to feminism (50). Experience and difference become integral to an understanding of the feminist rhetor.

The authors champion a feminist standpoint theory that would celebrate difference to the point that any marginalized person can benefit from this redefined notion of ethos, which requires listeners to identify with the speaker. This inverts Aristotle’s traditional concept of ethos in which the speaker attempts to persuade an audience by highlighting similarities. Donna Haraway cinches the redefined ethos in her epistemological turn to the multiplicity of the speaker, which would allow for splitting instead of being. After all, “subjectivity is multidimensional…always constructed and stitched together imperfectly, and therefore able to join with another, to see together without claiming to be another” (55).

Jarratt and Reynolds conclude with a brief application to the classroom. This reread ethos has pedagogical implications in that it can move student writing past the general audience and “Everyman” voice that students are accustomed to and comfortable with. With a framing of difference and multiplicity, teachers can encourage student writers to “split and resuture textual selves” through their writing (57). To me, this is dangerous territory as student identity constructs are largely unstable to begin with. There are ethical considerations for all theories we expose them to and encourage them to explore. Is it then unethical to potentially shake their identities in such a way? Or do we as instructors have a moral obligation to expose them to a myriad of identity theories as they are seeking their writing voice? This might be where a landscape for rhetoric of identity analysis.

Aristotle’s

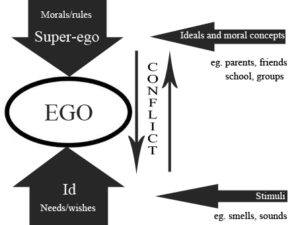

Aristotle’s  theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to

theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to