Sipiora, Phillip. “Ethical Argumentation in Darwin’s Origin of the Species.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1995, 265-292.

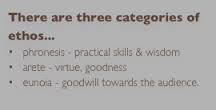

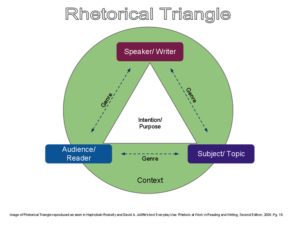

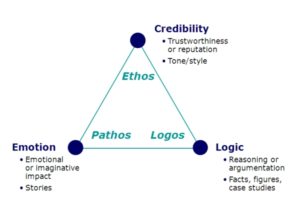

Sipiora, using a discourse analysis methodology, rhetorically analyses Darwin’s foundational  text, On the Origin of Species. Sipiora claims that this scientific discourse breaks traditions in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator (speaker) is constantly aware of and seeking to built a relationship of trust with the reader (audience). He does so using three of Aristotle’s subappeals: virtue (arete), goodwill (eunoia), and good sense (phronesis) (266).

text, On the Origin of Species. Sipiora claims that this scientific discourse breaks traditions in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator (speaker) is constantly aware of and seeking to built a relationship of trust with the reader (audience). He does so using three of Aristotle’s subappeals: virtue (arete), goodwill (eunoia), and good sense (phronesis) (266).

Virtue (arete) is found in Darwin’s passive constructions, establishment of professional integrity, patterns of self-effacement, third-person references, stative verbs, and catenative constructions. In utilizing these rhetorical devices, Darwin rests his dependence “on his attempts to involve the reader in the progressive development of the argument” (276). His “self-deprecating, self-correcting stance is a persuasive ethical strategy,” which Sipiora argues is key to his ethical argumentation (275).

Darwin’s use of goodwill (eunoia) is key in the “conjoining of rhetor and audience in a common endeavor” (276). This is accomplished through rhetorical devices such as identification rhetorical pronoun usage (we, our), rhetorical questioning, value appeals, first-person references (to highlight collective ignorance), and conditional clauses (if). Sipiora calls Darwin’s use of goodwill a “double-edged strategy…[and] a powerful rhetorical weapon…[for] simultaneous bonding with and manipulating of the reader” (279, 280).

Lastly, Darwin highlights good sense (phronesis) in his emphasis on probability. Comment clauses, integration of both first and third person pronouns (I, we), and strategic location of his argument within “accepted scientific investigation” all work together to “appeal to common sense” (282). Readers “are forced to rely on the good judgment of the expositor” because of our general lack of scientific knowledge and our ignorance exploited through these subappeals (287).

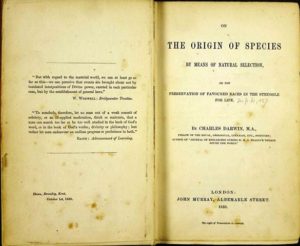

First Edition showing theological quotes by William Whewell & Francis Bacon

While Sipiora is not claiming that Darwin ignores pathos and logos, he is claiming that ethos was more important to Darwin in the writing of this text as “it is crucial that the scientific rhetor create a persona that emanates credibility” because of the time in which the book was published in 1859 (269). In fact, Darwin was so sure that the Church of the time would see the text as heretical, the first edition opened with two theological quotes to start establishing his credibility with his audience immediately. Sipiora ends by addressing the “so what” question: “Perhaps exploring the rhetoric of ethics in scientific texts will lead us to ask generative questions about ethical dimensions and implications far beyond the texts themselves” (288).

Sipiora’s multidisciplinary argument is unique in that it is analyzing a scientific text through a rhetorical lens. Typically, scientific discourse falls into the technical writing territory. Sipiora’s claim that Darwin’s text is in fact a rhetorical argument fits within the scope of Carolyn R. Miller’s claim that the positivist legacy of scientific discourse relaying Truth (uppercase implying absolute) isn’t valid. All writing is arguing for an interpretation of the world around us and is therefore arguing for truth (lowercase implying subjective). Considering Sipiora’s argument, Darwin’s text just might be proof of that claim.

I selected this article to demonstrate the rhetorical methodology of discourse analysis and because it deals with identification. In fact, Sipiora directly references Kenneth Burke’s identification: “The expositor-narrator must share some of the reader’s basic assumptions, what Kenneth Burke calls ‘identification,’ and it is this evolving identification with the reader that makes the Origin such a powerful rhetorical argument” (268). Burke’s theories of consubstantiality are of particular interest to me based on my personal course outcomes to explore major theorists and conversations surrounding rhetoric of identity.

Works Cited

Miller, C. R. “A humanistic rationale for technical writing.” College English, vol. 40, no. 6, 1979, pp. 610-617.

these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47).

these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47). Aristotle’s

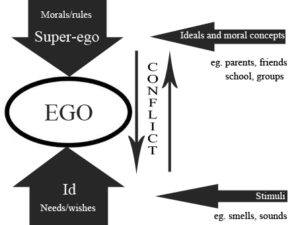

Aristotle’s  theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to

theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to