I suppose the guiding questions for this paper would firstly prompt a confession of my true  intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

What rhetorical elements were and are still at play in my own identity formation and what role do I play in the identity constructions, both actively and passively, of my students and those whom I interact with consistently? What role does society play on my identity and the identities of my students?

As we have firmly established already this semester, English is a multidisciplinary field. If we can not agree on any other definition, that fact is evident. This fact is precisely what led me to English and has continued to lure me back into the English classroom, both as student and teacher. Rhetoric is of particular interest to me because it seems to be the intersection of so many aspects of each subdiscipline. The texts of study and contexts of consideration of each subfield require attention to unique rhetorical situations, and the resulting identities are fascinating to me. Language, society and culture, power structures, ideologies–all of these converge through rhetoric and impact identity construction in multifarious ways. How are we ultimately defined by the ideologies embedded within each of the above listed aspects? And how are these ideologies translated to us as members of a myriad of communities at any given stage of our lives? It is for all of these reasons that I have narrowed my research energy this semester to rhetoric of identity.

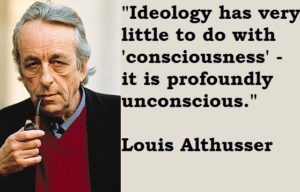

Althusser: Subjectivity and Ideology

In considering my own epistemological alignment, I find myself returning to Kenneth Burke’s term consubstantiality. Burke uses this term to describe someone who is both joined with and separate from another person or group. In our postmodern society, this seems to be how most people prefer to think of themselves in relation to any discourse community; we want to be part of a community but also maintain some level of independence and individuality. I also find myself more readily drawn to discussions of subjectivity, as Louis Althusser uses the term when describing the identity construct one assumes within an ideological framework. We are capable, to some extent, of role-playing or assuming some level of expected identity portrayal when functioning within an ideological framework, but are we also able to resist the identity constructions being placed upon us?

From my own personal experience as both a student and a teacher within religious school settings, the overlapping ideologies of religion and education demand a certain identity. When applying a Burkean lens to one K-12 school’s vision statement, these two ideologies converge into a specific identity construct that is expected of students: “to become godly warriors.” Rhetoric helps to maintain the constant tension between the two ideologies and enables the subjectivity of each student and faculty member who is consubstantial with the institution.

In looking through sources for this paper, I discovered quite a spectrum in relation to this conversation of rhetoric of identity. From Freud to Burke to Butler, the topic dips into multidisciplinarity quickly. Burke, a follower of Freud in many regards, believed that “the most fundamental human desire is social rather than sexual” as Freud often claimed (124). Another point of divergent thought in Burke and Freud is in Burke’s insistence that “there is no essential identity” (Davis 127). The identifying “I” becomes essentially an actor assuming the mores of a group as a means of identification. The underlying premise here is that there is “an ‘individual’ who is individuated by nature itself”; this estrangement between self and other Burke explains as biological (128). Overcoming this biological estrangement becomes the rhetorical job of identification.

This of course relates to the Hegelian concept of the Other as well as Judith Butler’s inclusion of otherness in queer theory. Karen Kopelson, utilizing Butler’s theories, seems to be on the other end of the spectrum from either Freud or Burke: no intrinsic identity or self. Freud, claiming there is an intrinsic sexual self, forms one end of the spectrum; Burke, believing in an estranged biological self that is influenced socially, plots another point, perhaps near the middle of the spectrum, while Butler and Kopelson are on the other end of this identity spectrum: identity is performative.

This provides quite the array to consider when seeking my own epistemological alignment. Because my learning outcomes are often connected, at least partially, to my own identity as an educator, my Objects of Study are often students themselves and connecting artifacts, such as school handbooks and vision and mission statements. The pedagogical basis of Kopelson’s argument caught my attention for that reason. However, I was left questioning the ethical implications of a queer pedagogical approach that has “the express intention of disrupting students’ identity-based expectations” or that attempts to keep “them [students] ‘off balance’ by deliberately shifting among and between positions of provocative skepticism and fervent belief” (20, 25). As one instructor within Kopelson’s example stated, some students need an essentialist identity for a time of transition into a more unstable mindset. Are teenagers cognitively and emotionally able to deal with this level of instability?

These residual questions imply that I do not align in all regards with queer theory approaches. I do, however, believe that Burke was onto something with his discussion of identity being largely molded by society and Althusser’s notions of ideological implications in identity construction. Butler also speaks to gender being a social construct, so in that regard I do agree with her theories. I believe that I align somewhere within this Marxist camp in its emphasis of power structures and ideological influence, although I obviously do not subscribe to all Marxist tenets.

Ultimately, I am fascinated in language’s power, no matter the theoretical lens, to impact identity construction in ways of which an individual is not even aware. I hope to find a niche in researching student identity constructs as one of my primary objects of study. Perhaps, through my research process, I will start to understand my own identity…here’s to hoping!

Works Cited

Althusser, Louis. “From Ideology and State Apparatuses.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 1335-1360.

Burke, Kenneth. “From A Rhetoric of Motives.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, 1324-1340.

Davis, Diane. “Identification: Burke and Freud on Who You Are.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2008, pp. 123-147, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02773940701779785. Accessed 12 Oct. 2016.

Kopelson, Karen. “Dis/Integrating the Gay/Queer Binary: ‘Reconstructed Identity Politics’ for a Performative Pedagogy.” College English, vol. 65, no. 1, pp.17-35, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3250728. Accessed 12 Oct. 2016.