Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods–these are the standard research methods that come to mind when considering scholarly research. For the field of rhetoric, perhaps rhetorical analysis, a staple essay for any secondary writer or freshman composition syllabus. But rhetorical studies contains a myriad of diverse methods that are more specialized to individual research projects.

Before looking at some of these, it is important to note the subtle differences between methods and methodologies. While methods are the practices employed to analyze a text or to gather data, Sullivan and Porter highlight the bias that any researcher brings to a project through a chosen methodology, for it is a “rhetorical invention…[a] rhetorical interaction…it is itself an act of rhetoric” (10, 12, 13). A methodological framework is coupled with an ideology that is largely unavoidable; this is why a researcher must be careful in methodology selection and must be open about the resulting implications of that choice upon the research. Sullivan and Porter go further to claim that methodologies need to be reflexive and flexible in order to fit the given research text or situation (70).

Rhetoric is a sub-discipline that permeates so many others and its methodologies and theories are fairly vast, at least in their application.

“Lauer,” in our course text, claims “the field’s methodology as multimodal. Prominent among these modes of inquiry have been historical studies; theory building; empirical research (from qualitative studies like ethnographies to quantitative studies like experiments and meta-analyses); discourse analysis and interpretative studies, feminist and teacher research; and postmodern investigations” (132).

This list serves as a starting point for identifying and categorizing the array of research that rhetoricians do, as well as rhetorical methods employed by other disciplines.

Ryan Lee Teten, a rhetorical scholar of political communication, uses rhetorical analysis to do historical inquiry within the field of political science to look at “the ‘traditional/modern’” paradigm as it relates to the speech category of the State of the Union address. His method is a “line-by-line content analysis through all of the State of the Union Addresses from George Washington to George W. Bush to count elements such as word length, specific word usage, and context” (671). These categories are designed to highlight both audience in address to congress vs. the people and speaker in identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Teten concludes that “contemporary presidents use identification rhetoric [we, us, our] in amounts never before seen in the State of the Union Address…[and] that presidential rhetoric may not be easily categorized as simply ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’” (675, 670-671).

His multidisciplinary methodological approach allows for shared data and terms that can bring much to conversations in both Political Science and English Studies. The methodology of historical inquiry allows the method of rhetorical analysis to highlight both the importance of the language and the historical figures. I do wonder what a similar analysis of Donald Trump’s and Hillary Clinton’s stump speeches and debates would reveal in using Teten’s same lens of identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Would they align with our founding fathers in any ways or further the traditional/modern divide?

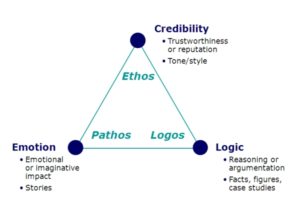

Phillip Sipiora uses discourse analysis to rhetorically analyse Darwin’s foundational text, On the Origin of Species. Sipiora claims that this scientific discourse breaks traditi ons in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator (speaker) is constantly aware of and seeking to built a relationship of trust with the reader (audience). In hearkening back the historical roots of the field, the author does so using three of Aristotle’s subappeals: virtue (arete), goodwill (eunoia), and good sense (phronesis) (266). While Sipiora is not claiming that Darwin ignores pathos and logos, he is claiming that ethos was more important to Darwin in the writing of this text as “it is crucial that the scientific rhetor create a persona that emanates credibility” because of the time in which the book was published in 1859 (269). Sipiora concludes, “Perhaps exploring the rhetoric of ethics in scientific texts will lead us to ask generative questions about ethical dimensions and implications far beyond the texts themselves” (288).

ons in moving away from the conventions of scientific demonstrations as Darwin writes an ethical argument or a “quasi-scientific treatise” (266). The expositor-narrator (speaker) is constantly aware of and seeking to built a relationship of trust with the reader (audience). In hearkening back the historical roots of the field, the author does so using three of Aristotle’s subappeals: virtue (arete), goodwill (eunoia), and good sense (phronesis) (266). While Sipiora is not claiming that Darwin ignores pathos and logos, he is claiming that ethos was more important to Darwin in the writing of this text as “it is crucial that the scientific rhetor create a persona that emanates credibility” because of the time in which the book was published in 1859 (269). Sipiora concludes, “Perhaps exploring the rhetoric of ethics in scientific texts will lead us to ask generative questions about ethical dimensions and implications far beyond the texts themselves” (288).

Sipiora’s argument, with its emphasis on both the rhetor and the audience, rests upon a foundational theory to the field of rhetoric. It also addresses some of the field’s major questions when it comes to analyzing identity portrayal and perceptions, both points of interest in my own course outcomes. The major questions of the rhetor’s intentions and identity as determined by the audience, as well as the challenges facing the rhetor in establishing an identity construct necessary to successfully persuade an audience, are all addressed by Sipiora in the discourse analysis of Darwin’s text (Depew).

Sipiora’s article is of further interest to me because of the author’s direct references to Kenneth Burke’s identification: “The expositor-narrator must share some of the reader’s basic assumptions, what Kenneth Burke calls ‘identification,’ and it is this evolving identification with the reader that makes the Origin such a powerful rhetorical argument” (268). Burke’s theories of consubstantiality are of particular interest to me based on my personal course outcomes to explore major theorists and conversations surrounding rhetoric of identity.

While empirical research, with its ties to scientific writing, has been more authoritative in the past, feminist studies has become more dominant in rhetorical conversations over the past couple of decades. Within this, historical inquiry and discourse analysis have been utilized. For example, our class discussion and course reading on Aspasia involved both methodologies in building from questions of our field’s established history and the gaps in canonized texts. Current trends are building upon the momentum of feminist studies to embrace queer studies not just in the sub-discipline of rhetoric, but throughout the field of English studies. These methodological trends provide theoretical frameworks for much of my objects of study relating to identity constructs.

Works Cited

Depew, Kevin. Personal interview. 5 October 2016.

Lauer, Janice M. “Rhetoric and Composition.” English Studies: An Introduction to the Discipline(s), edited by Bruce McComiskey, National Council for Teachers of English, 2006, 106-152.

Miller, C. R. “A humanistic rationale for technical writing.” College English, vol. 40, no. 6, 1979, pp. 610-617.

Sipiora, Phillip. “Ethical Argumentation in Darwin’s Origin of the Species.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1995, 265-292.

Sullivan, P. A., & Porter, J. E. Opening spaces: Writing technologies and critical research practices. Ablex, 1997, 1-13, 45-99.

Teten, Ryan Lee. “‘We the People’: The ‘Modern’ Rhetorical Popular Address of the Presidents during the Founding Period.” Political Research Quarterly, vol. 60, no. 4, Dec. 2007, pp. 669-682. Ebscohost, doi: 10.1177/1065912907304495. Accessed 27 Oct. 2016.

text,

text,

of this research, he defines rhetorical leadership “as the process of discovering, articulating, and sharing the available means of influence in order to motivate human agents in a particular situation…it is leadership exerted through talk or persuasion” (Dorsey as qtd. on 670). His method is a “line-by-line content analysis through all of the State of the Union Addresses from George Washington to George W. Bush to count elements such as word length, specific word usage, and context” (671). These categories are designed to highlight both audience in address to congress vs. the people and speaker in identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Teten concludes “that presidential rhetoric may not be easily categorized as simply ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’” (670, 671).

of this research, he defines rhetorical leadership “as the process of discovering, articulating, and sharing the available means of influence in order to motivate human agents in a particular situation…it is leadership exerted through talk or persuasion” (Dorsey as qtd. on 670). His method is a “line-by-line content analysis through all of the State of the Union Addresses from George Washington to George W. Bush to count elements such as word length, specific word usage, and context” (671). These categories are designed to highlight both audience in address to congress vs. the people and speaker in identification, authority, and directive rhetoric. Teten concludes “that presidential rhetoric may not be easily categorized as simply ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’” (670, 671). Zarefsky’s

Zarefsky’s intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47).

these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47). Aristotle’s

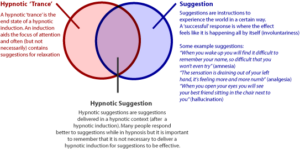

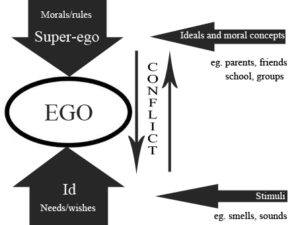

Aristotle’s  theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to

theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to  On the other hand, distinctions that do matter point to four senses evolving from the term

On the other hand, distinctions that do matter point to four senses evolving from the term