Aristotle’s Rhetorical Situation

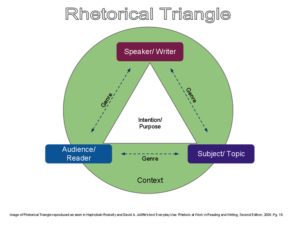

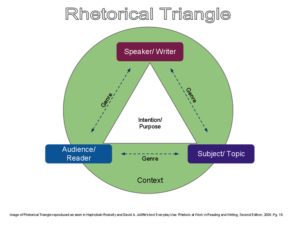

While the major questions utilized by rhetoricians of identity have largely branched out into various directions, the common foundation does harken back to the classical concept of the rhetorical situation. The rhetor and the audience are the dominant points of connectivity when it comes to analyzing identity portrayal and perceptions. These two focal points highlight two of the major questions:

- What are the rhetor’s intentions and how does he/she want to be perceived?

- How much of the rhetor’s identity is determined by the audience? (Depew).

Each of these inquiries yields a series of sub-questions.

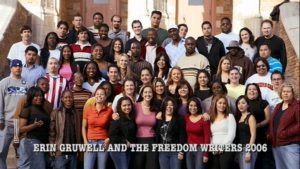

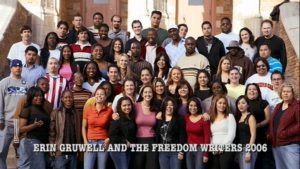

When analyzing a rhetor’s intentions and identity portrayal, Aristotelian questions arise: what rhetorical tools are available to the rhetor and to what extent is he/she using those tools to persuade an audience? What challenges does the rhetor face in establishing the identity construct necessary to successfully persuade an audience (Depew)? For example, a white, young female teacher may have a difficult time in teaching a largely black/minority high school class because these audience members might associate with a certain people group. Take the nonfiction story of Freedom Writers. Erin Gruwell, the highlighted teacher, struggles to gain the trust of her “audience,” in this case a classroom full of students, because she does not look like them and is in an authority position of which they have come to be leery. Her rhetorical tools revolve around reaching into her students’ culture and pulling out artifacts to which they can relate and from which they can learn through familiar out-of-school literacies.

Sub-questions surrounding the analysis of the audiences’ perceptions of any given rhetor involve an audience’s awareness of social context. Does the audience see the rhetor’s identity as enacted through the social context? Does the audience see the rhetor’s identity as monolithic or fragmented, meaning reliant upon the rhetorical situation at hand (Depew)? This second question can also be inverted and applied back to the rhetor as well.

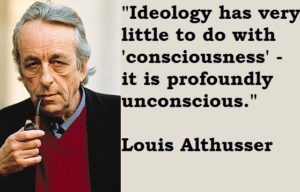

These issues stemming from the rhetorical situation also point to questions of terminology. One term used in these conversations is consubstantiality, popularized by Kenneth Burke through his rhetorical theories of identity. Burke uses this term to describe someone who is both joined with and separate from another person or group. Louis Althusser uses subjectivity when describing the identity construct one assumes within an ideological framework. These more recent terms were preceded by Aristotle’s concept of ethos, which has probably changed and evolved the most over the past 2,000+ years. While Aristotle originally used the term as a site of persuasion, scholars and theorists have tailored the definition to modern culture and individual research projects. Susan C. Jarratt and Nedra Reynolds, for example, trace various uses of the term ethos etymologically. They “reread classical ethos through feminist history,” which reveals that while older definitions of ethos point to customs or habits, newer notions point to character (40). Ultimately, their rereading allows for a classical notion of ethos that will acknowledge difference and therefore give voice to feminism (50). Experience and difference become integral to an understanding of the feminist rhetor.

With a slightly different angle on the term ethos, Marshall W. Alcorn Jr. argues for a definition of “ethos as a relationship existing between the discourse structures of selves and the discourse structures of ‘texts’” (6). Aristotle’s ethos implies that an audience, always passive, can be persuaded by the mere character of the speaker. His primary claim is that the self is ultimately a rhetorical entity as the two act upon one another: “The self is stable enough to resist change and changeable enough to admit to rhetorical manipulation but not so changeable as to constantly respond, chameleonlike, to each and every social force” (17). These changes require effective rhetoric with stylistic devices tailored to an audience well-researched. Alcorn deals with not only the question of terms and definitions, but also with the sub-question relating to rhetor’s identity as reliant upon social and rhetorical context and fragmented rather than monolithic.

Feminist scholars and queer theorists have also recently taken up the conversation and given the research questions related to rhetorical identity constructs a gender focus. Judith Butler, for example, asks how identity is ultimately established through performative acts. Jacques Lacan questions society’s role in identity construction. Ultimately, while major

Barthes’ “The Death of the Author”

questions connected to identity constructs do still point to the foundational rhetorical situation, there has been a significant postmodern shift away from the rhetor’s intention and intended identity portrayal. Roland Barthes, for example, in “The Death of the Author” puts all the interpretive power in the hands of the audience. These might be the most significant historical shifts in major questions from Aristotle to current theorists: agency now lies with the audience and society.

My personal learning outcomes are always connected in part to how I can apply theory to my own pedagogy to improve practice in my classroom. Jarratt and Reynolds’ reread ethos has pedagogical implications in that it can move student writing past the general audience and “Everyman” voice that students are accustomed to and comfortable with. With a framing of difference and multiplicity, teachers can encourage student writers to “split and resuture textual selves” through their writing (57). To me, this is dangerous territory as student identity constructs are largely unstable to begin with. There are ethical considerations for all theories we expose students to and encourage them to explore. Is it then unethical to potentially shake their identities in such a way? Or do we as instructors have an ethical obligation to expose them to a myriad of identity theories as they are seeking their writing voice? This might be a landscape for rhetorical analysis of identity.

Works Cited

Alcorn, Marshall W. Jr. “Self-Structure as a Rhetorical Device: Modern Ethos and the Divisiveness of the Self.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1995, 3-35.

Althusser, Louis. “From Ideology and State Apparatuses.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 1335-1360.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 1322-1326.

Burke, Kenneth. “From A Rhetoric of Motives.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, 1324-1340.

Butler, Judith. “From Gender Trouble.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 2540-2552.

Depew, Kevin. Personal interview. 5 October 2016.

Jarratt, Susan C., and Nedra Reynolds. “The Splitting Image: Contemporary Feminisms and the Ethics of ethos.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1995, 37-63.

Lacan, Jacques. “From The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 1169-1180.

from which to pull objects of study.

from which to pull objects of study.  intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.