A Historical Snapshot of Rhetoric of Identity: From Male-Dominated to Feminist-Focused

Trying to find a starting point for rhetorical discussion dedicated to identity has proven to be somewhat problematic as it is not actually a sub-discipline or a topic that scholars have solely dedicated their research to. Most embed or imply rhetoric of identity in larger studies and conversations. In fact, over time, schisms have arisen that assume a specific rhetorical identity stance through which to claim ethos and enter an ongoing conversation. Take feminist studies for example: Elaine Showalter, Barbara Smith, Judith Butler, and many more have established an identity construct that allows a rhetorical stance to be assumed and analysis to be done within the discourse community associated with that particular identity. Yet while the history is spotty and one must pull back layers, there is a rich history there.

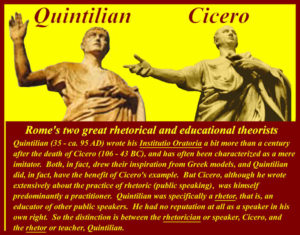

I would think it remiss if one did not include Quintilian and Cicero somewhere close to  beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” (qtd. in Katz 255). The identity of the rhetorician was rarely divorced from the character of the speaker as the quality of skill was often associated with the integrity of a man.

beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” (qtd. in Katz 255). The identity of the rhetorician was rarely divorced from the character of the speaker as the quality of skill was often associated with the integrity of a man.

While this tradition lasted for quite some time, recently feminist scholars have challenged most if not all of the notions established by the males of our canon. Tita French Baulmin declares “a good woman speaking well” should also be granted a voice in this conversation of identity. With a specific research focus on the Renaissance era, not ironically known for the “Renaissance man” rather than woman, she claims that the phrase would be considered a contradiction. In calling on the rhetorical identity term ethos, she claims that “Ethos as the site of ideological battle will always show traces of capitulations to, and exploitations of, both authority and Other” (253). Using Elizabeth I, she argues that to identity her as an “honorary male” based on her rhetoric would be an eradication of identity.

Baulmin’s conversation brings together two historically significant aspects to the rhetoric of identity conversation: the variants in terminology and the concept of the Other. Ethos, while most commonly associated with Aristotle’s appeals, can be ascribed to “personal or collective identity” (Zulick 20). Kenneth Burke, my personal point of interest in this historical  conversation, uses the term consubstantial to describe someone who is both joined with and separate from another person or group. This, he claims, is “the source of dedications and enslavements” (qtd. in Bizzell and Herzberg 1325). Hegel introduced the concept of the Other, in which one can only truly understand one’s self through interactions with and comparisons to another (541). This has been carried over into more current conversation of gender and sex in the fields of feminist and queer studies.

conversation, uses the term consubstantial to describe someone who is both joined with and separate from another person or group. This, he claims, is “the source of dedications and enslavements” (qtd. in Bizzell and Herzberg 1325). Hegel introduced the concept of the Other, in which one can only truly understand one’s self through interactions with and comparisons to another (541). This has been carried over into more current conversation of gender and sex in the fields of feminist and queer studies.

For feminist scholars such as Cheryl Glenn, historiography cannot be accurately accomplished without the joint perspectives of gender studies and feminism, two sub-disciplines vital today to any rhetorical discussion of identity (288). Most relevant discussions will most likely adopt a multidisciplinary approach to identity, making rhetoric one of several angles. In fact, Zarefsky, in mapping out four senses of rhetorical history, also speaks to the multidisciplinary nature of most methodologies and modes of inquiry. My approach to this research on rhetoric of identity seems to best fit within his sense of the rhetoric of history because of the ideological implications of identity constructs (27-28).

Most aspects to any identity are going to be largely constituted through language. From Quintilian to Burke to more recent contributions to the conversation, like Lacan (identity as being a social construct) and Butler (identity as a series of performative actions), the conversations of rhetoric of identity are still finding the right words through which to discuss this interdisciplinary topic. The university system as a whole employs rhetoric of identity continuously as faculty members, students, and sports fans alike make themselves consubstantial with the ideals of their chosen institution. Our current political season has encouraged attention once again to the topic of rhetoric of identity as citizens seek out a place in which to have a voice that is heard through a candidate to whom they might identity. In these ways, rhetoric of identity goes beyond the walls of any university.

Works Cited

Baulmin, Tita French. “‘A Good (Wo)Man Skilled in Speaking’: Ethos, Self-Fashioning, and Gender in Renaissance England.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1994, 229-263.

Bizzell, Patricia, and Bruce Herzberg. “Quintilian.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, 359-364.

Burke, Kenneth. “From A Rhetoric of Motives.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, 1324-1340.

Glenn, Cheryl. “Remapping Rhetorical Territory.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 13, no. 2, Spring 1995, pp. 287-303. JSTOR. Sept. 14, 2016.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. “From Phenomenology of Spirit.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 541-547.

Katz, S. B. “The ethic of expediency: Classical rhetoric, technology, and the Holocaust.” College English, vol. 54, no. 3, 1992, pp.255-275. JSTOR. Oct. 4, 2008.

Zarefsky, David. “Four Senses of Rhetorical History.” Doing Rhetorical History: Concepts and Cases. Ed. Kathleen J. Turner. University of Alabama Press, 1998, 19-32.

Zulick, Margaret D. “The Ethos of Invention: The Dialogue of Ethics and Aesthetics in Kenneth Burke and Mikhail Bakhtin.” The Ethos of Rhetoric, edited by Michael J. Hyde, University of South Carolina Press, 2004, 20-33.

Sarah, this was a fascinating read — until last week, I really had no idea of the scope of the field. I think you wrangled this massive history into a compact nugget that’s fun to read, so kudos!

I specifically came to your essay to comment because I appreciate how you bring this forward to today’s political climate. What you say and how you say it are simply too critical to be taken lightly. Structure and form obviously matter. I would like to think that rhetoricians are having a field day with this — I’ve read one essay on the subject, and it was fascinating. This is definitely a subject I need to learn a lot more about.

While reading your paper, I can’t help but hearken back to Glenn’s attempt to identify the historical impact of Aspasia’s influence on the “male-dominated” art or rhetoric. As you note, Cicero and Quintilian play an enormous role in rhetoric’s inception and flowering, but Aspasia’s mysterious identity could definitely fill a void regarding women in the conversation. Of course, as we have seen/read, establishing an identity construct for someone who may not even have existed is a challenge.

Your discussion of feminists challenging the notions established by the males in our canon reminds me of last week’s class, Sarah. It seems that without female voices in the canon, there is a significant gap not only in our scholarship, but also in our understanding of history, culture, and, of course, identity. You’ve prompted me to take a closer look at the subdiscipline of gender studies in order to gain a broader vocabulary and a deeper understanding of potential gaps in rhetoric that exist as a result of our male-dominated canon.