Alcorn, Marshall W. Jr. “Self-Structure as a Rhetorical Device: Modern Ethos and the Divisiveness of the Self.” Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist University Press, 1995, 3-35.

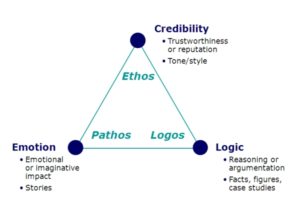

Alcorn argues for a reconception of ethos in both building upon and moving away from traditional (Aristotelian) definitions of ethos and poststructuralist (Rorty) definitions of the self. He argues for a definition of “ethos as a relationship existing between the discourse structures of selves and the discourse structures of ‘texts’” (6). The ancient Greek understanding of the self was conceptualized more as a character, defined and enacted by society.  Aristotle’s ethos implies that an audience, always passive, can be persuaded by the mere character of the speaker. Rorty goes further in defining the components of any self-structure as an evolution of four entities: character, person, self, and individual. It is not until the final stage, the individual, that one is free to select his or her identity construct. Alcorn agrees with the notion that “history shapes selves,” but the self is not passively shaped as it “can dialectically engage and resist…social interaction (12, 14). His main claim is that the self is ultimately a rhetorical entity as the two act upon one another: “The self is stable enough to resist change and changeable enough to admit to rhetorical manipulation but not so changeable as to constantly respond, chameleonlike, to each and every social force” (17). These changes require effective rhetoric with stylistic devices tailored to an audience well-researched.

Aristotle’s ethos implies that an audience, always passive, can be persuaded by the mere character of the speaker. Rorty goes further in defining the components of any self-structure as an evolution of four entities: character, person, self, and individual. It is not until the final stage, the individual, that one is free to select his or her identity construct. Alcorn agrees with the notion that “history shapes selves,” but the self is not passively shaped as it “can dialectically engage and resist…social interaction (12, 14). His main claim is that the self is ultimately a rhetorical entity as the two act upon one another: “The self is stable enough to resist change and changeable enough to admit to rhetorical manipulation but not so changeable as to constantly respond, chameleonlike, to each and every social force” (17). These changes require effective rhetoric with stylistic devices tailored to an audience well-researched.

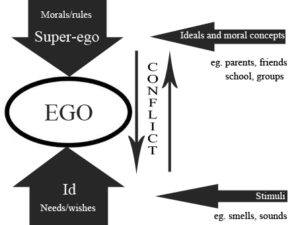

The above theoretical considerations carry implications for a revision to the signified associated with the signifier ethos. While Alcorn isn’t claiming that either approach (Aristotelian or poststructuralist) is outdated, he is saying they are restrictive in light of the “prodigious diversity, plurality, and multiplicity” of our modern culture (18). These cultural characteristics have yielded a society full of divided, conflicted, and anxious selves. In utilizing a multidisciplinary approach, Alcorn taps into psychoanalysis through Freud’s ego  theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to sociological theories of leadership in the charismatic leader; it is the charismatic leader who is a “master of ethos” as he or she can communicate self (24). All of these discussions ultimately point to a modern ethos that is an “aesthetic manipulation of self-division” (28).

theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to sociological theories of leadership in the charismatic leader; it is the charismatic leader who is a “master of ethos” as he or she can communicate self (24). All of these discussions ultimately point to a modern ethos that is an “aesthetic manipulation of self-division” (28).

Literature and critical theory also reflect this modern concept of the divided self. In fact, Alcorn dedicates several pages to an analysis of Orwell’s essay “Shooting an Elephant” to highlight the potential available to an author (or speaker) with a modern ethos. Lastly, Alcorn discusses the pedagogical implications of such a revision to the concept of ethos. If teachers can facilitate class discussions so as to tap into the self-structures of our modern culture’s divided student identities, rhetoric can impact change to these learning selves.

Alcorn’s argument is in response to some of the basic research questions surrounding the topic of rhetoric of identity: How does rhetoric connect to and affect/impact identity? He personalizes this question to seek out a relationship between the self and language that leads him to a conclusion that the two (rhetoric and identity) are co-dependent: one yields the other and vice versa.

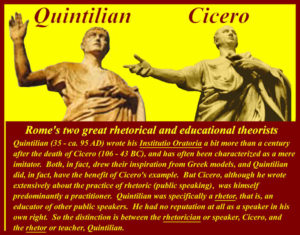

beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” (

beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” ( conversation, uses the term

conversation, uses the term  On the other hand, distinctions that do matter point to four senses evolving from the term

On the other hand, distinctions that do matter point to four senses evolving from the term  so far. For example, Nugent and Ostergaard’s distinction between preservation and transformation is a different aspect of the same conversation. The very nature of English studies is rooted in an ever-changing history with dynamic boundaries that span disciplines from communication and linguistics to the pragmatic sub-fields of composition and pedagogy. McComiskey talks directly about the topic of identification in calling for integration within the field of English studies. Miller discusses the four disciplinary corners that make up the ambiguous field of English studies. Glenn’s discussion falls right in line with these concepts. To point to a static history would be a mistake as undoubtedly, there are still aspects, or angles to borrow Glenn’s terminology, yet veiled to our current modes of inquiry and research methodologies as they are fluid and even undefined in some sub-fields.

so far. For example, Nugent and Ostergaard’s distinction between preservation and transformation is a different aspect of the same conversation. The very nature of English studies is rooted in an ever-changing history with dynamic boundaries that span disciplines from communication and linguistics to the pragmatic sub-fields of composition and pedagogy. McComiskey talks directly about the topic of identification in calling for integration within the field of English studies. Miller discusses the four disciplinary corners that make up the ambiguous field of English studies. Glenn’s discussion falls right in line with these concepts. To point to a static history would be a mistake as undoubtedly, there are still aspects, or angles to borrow Glenn’s terminology, yet veiled to our current modes of inquiry and research methodologies as they are fluid and even undefined in some sub-fields.