Davis, Diane. “Identification: Burke and Freud on Who You Are.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2008, pp. 123-147, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02773940701779785. Accessed 12 Oct. 2016.

Davis highlights some distinctions between Burke’s theories of identity, largely centered upon symbolic acts that result in consubstantiality, and Freud’s psychoanalytic connections of the narcissist self and the other. Burke was heavily influenced by Freud, yet does move decisively away from Freudian notions at a couple points. These points of divergence largely center on Burke’s insistence that “Identification is compensatory to division” (123). Furthermore, Burke believes that “the most fundamental human desire is social rather than sexual,” as Freud often claimed (124).

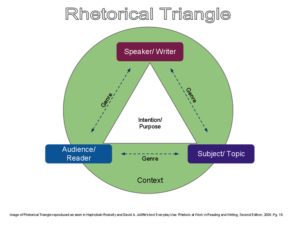

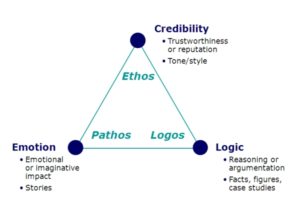

Burke, the father of modern rhetoric, was well-versed in Aristotelian foundations of rhetoric being primarily an act of persuasion. Burke took that foundation and went further, claiming “that any persuasive act is first of all an identifying act” (125). This is where his term consubstantial is introduced, for one is both joined with and separate from another in most instances of identification. It is important to Burke that complete unity is not established as this unity would negate the need for any rhetorical/symbolic act. The ability to resist complete unity comes through human capability for critique and logic and rests in “the productive tension between fusion and division” (126).

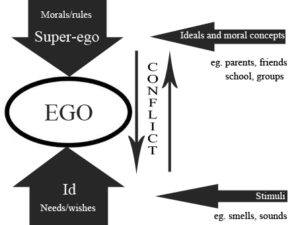

Where one can find a point of divergent thought in Burke and Freud is in Burke’s insistence that “there is no essential identity” (127). The identifying “I” becomes essentially an actor assuming the mores of a group as a means of identification. The underlying premise here is that there is “an ‘individual’ who is individuated by nature itself”; this estrangement between self and other Burke explains as biological (128). Overcoming this biological estrangement becomes the rhetorical job of identification.

Davis briefly turns to the neuroscience behind much of these theories; mirror neurons in the brain actually do not make a distinction when I pick up a pencil or when I see someone else pick up a pencil. The same neurons fire. This unravels some of Burke’s presumptions. Another point of Burkean divergence rests upon Freud’s argument that identity constructs, perhaps better qualified as dis-identifications as they are identity constructs formed through disassociations, formed in the oral stage largely stick. Yet, one can see Burke and Freud converging once again in Freud’s second stage, that is largely social in nature, and in their theoretical bases on an ontological self with desires:

“So although Burke challenges psychoanalytical criticism for reducing the desire for social intercourse to a sexual desire, he is very much with the ‘official’ Freud in his refusal to question the ontological priority of desire itself, which, despite it all, presumes a subject who has desires, be they conscious or unconscious” (130).

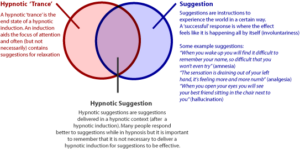

Freud introduced Hypnosis and claimed that suggestion was magically powerful usage of language

Through an explanation of hypnosis and the power of language used throughout the hypnotic process, Davis highlights the fact that Burke only briefly and without true explanation deals with the “rhetoric of hysteria.” This points to yet another point of divergence, albeit minor, in that Freud champions the “magic” of language’s power through suggestion, the rhetorical process of hypnotizing someone, which becomes a “fundamental problem” for rhetorical theory (142). Burke maintains “an almost absolute faith in the power of reason” in spite of one’s capacity for hysteria or ability to be manipulated through the power of suggestion. Davis concludes that, ultimately, “the[ir] disagreement is in the details” (125).

This article fits the context of our course outcomes in that it highlights the interdisciplinary nature of the field. Burke’s rhetorical theories are largely rooted in the field of psychology with their overt nod to Freud. Throughout Davis’s discussion, she references Heidegger, Lacan, and Butler, pointing to the interconnectivity of not only our field but theories within the field. This article also gives me some context for my own learning goals of re-familiarizing myself with rhetoric of identity and the key players and terms within that conversation.

these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47).

these sophists connect character formation to adjusting community standards. This, basically the work of ideology, creates a space for an alliance between sophistic rhetoric and feminism (47). Aristotle’s

Aristotle’s  theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to

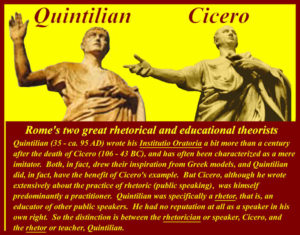

theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to  beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” (

beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” ( conversation, uses the term

conversation, uses the term  On the other hand, distinctions that do matter point to four senses evolving from the term

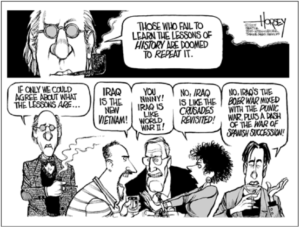

On the other hand, distinctions that do matter point to four senses evolving from the term  so far. For example, Nugent and Ostergaard’s distinction between preservation and transformation is a different aspect of the same conversation. The very nature of English studies is rooted in an ever-changing history with dynamic boundaries that span disciplines from communication and linguistics to the pragmatic sub-fields of composition and pedagogy. McComiskey talks directly about the topic of identification in calling for integration within the field of English studies. Miller discusses the four disciplinary corners that make up the ambiguous field of English studies. Glenn’s discussion falls right in line with these concepts. To point to a static history would be a mistake as undoubtedly, there are still aspects, or angles to borrow Glenn’s terminology, yet veiled to our current modes of inquiry and research methodologies as they are fluid and even undefined in some sub-fields.

so far. For example, Nugent and Ostergaard’s distinction between preservation and transformation is a different aspect of the same conversation. The very nature of English studies is rooted in an ever-changing history with dynamic boundaries that span disciplines from communication and linguistics to the pragmatic sub-fields of composition and pedagogy. McComiskey talks directly about the topic of identification in calling for integration within the field of English studies. Miller discusses the four disciplinary corners that make up the ambiguous field of English studies. Glenn’s discussion falls right in line with these concepts. To point to a static history would be a mistake as undoubtedly, there are still aspects, or angles to borrow Glenn’s terminology, yet veiled to our current modes of inquiry and research methodologies as they are fluid and even undefined in some sub-fields.