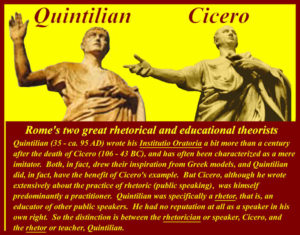

What does it take to be a scholar of…well, anything? I don’t know that I have ever truly paused to think this through before as I am a person who is always pushing towards the next thing, whether that is the next paper, class, degree, or even just the next weekend. Yet, this course of study has made it is clear that to be a scholar of anything requires a foundational knowledge of the history. For  my chosen research topic of rhetoric of identity, Quintilian and Cicero represent just a few of the males who dominated the rhetorical tradition early on. Both rhetors stressed the character of the speaker: Quintilian with his mantra of “A Good Man Speaking Well” and Cicero with his emphasis on the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom” (Bizzell & Herzberg 359; qtd. in Katz 255). It wasn’t until the last half a century that women began to emerge from the patriarchal structure of rhetoric’s past. Key scholars like Glenn and Gale gave Aspasia a voice, and others such as Showalter and Butler have furthered the push to restore marginalized voices to the canon.

my chosen research topic of rhetoric of identity, Quintilian and Cicero represent just a few of the males who dominated the rhetorical tradition early on. Both rhetors stressed the character of the speaker: Quintilian with his mantra of “A Good Man Speaking Well” and Cicero with his emphasis on the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom” (Bizzell & Herzberg 359; qtd. in Katz 255). It wasn’t until the last half a century that women began to emerge from the patriarchal structure of rhetoric’s past. Key scholars like Glenn and Gale gave Aspasia a voice, and others such as Showalter and Butler have furthered the push to restore marginalized voices to the canon.

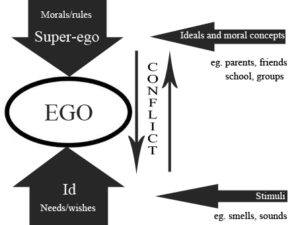

But it isn’t the history alone that defines rhetoric of identity. While rhetorical scholars are still asking similar major questions about the identity of the rhetor and the audience (Depew), the objects of study have expanded to include both human and non-human texts. From online identity constructions to the physical body, nearly anything can be rhetorically crafted and therefore analyzed. Through my research this semester, I surprisingly found my own epistemological alignment somewhere near the camp of the Marxists. Althusser, for example, claims that ideologies are ever-present and are constantly acting upon us, molding and making us who we are (1335-1360). Why not rhetorically analyze who we are then in an effort to unveil some of these ideological implications upon our own identity constructs?

This is the root reason for my research interest. My own upbringing in a Christian  school was volatile in many ways as worldviews clashed around me and much was determined for me. I am grateful for many reasons for the protective environment in which I was raised and in which I now find myself as a faculty member. However, my role as teacher now affords me a different perspective on these ideological forces, and I feel a responsibility to my students to act as a catalyst for them, to expose them to ideas beyond the horizon of the tension-filled ideologies of religion and education. For in these types of institutions, much as Foucault claims, their identities have been largely determined for them through the language of the mission statement, daily procedures, schedules, curriculum objectives, etc.

school was volatile in many ways as worldviews clashed around me and much was determined for me. I am grateful for many reasons for the protective environment in which I was raised and in which I now find myself as a faculty member. However, my role as teacher now affords me a different perspective on these ideological forces, and I feel a responsibility to my students to act as a catalyst for them, to expose them to ideas beyond the horizon of the tension-filled ideologies of religion and education. For in these types of institutions, much as Foucault claims, their identities have been largely determined for them through the language of the mission statement, daily procedures, schedules, curriculum objectives, etc.

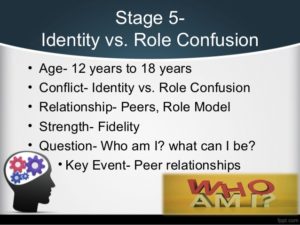

These reflections, on both my own identity and those largely pre-determined identities of my students, keeps me coming back to these rhetorical theories of identification. Kenneth Burke’s theories of consubstantiality, of being both joined with yet separate from, seems to be a potential key to guiding my students to self-discovery through the ways in which I design my own course assignments and frame my discourse communities, into which I invite my students (1325). Student identity constructs are my object of study, primarily because students are my passion. Knowledge and a clashing of worldviews, ideologies, and theories has been transformative for me, and it is that transformation that I hope for my students.

The pedagogical implications of rhetoric of identity are never-ending. From Karen Kopelson’s move away from identity-based pedagogical approaches to Erin Gruwell’s less-than-formalized rhetorical choices to connect with her student audience, teachers posses a great power and responsibility to create an atmosphere where students are comfortable to explore and to create their own identities (Kopelson 17-35). For some, this will be major as they question their sexuality and gender associations. For others, it might mean they process the familiar identity constructs of their close friends and family members and decide that is exactly where they fit with their own identity. Wherever each student may fall, this is my civic rhetoric: my rhetorically-designed classroom for identity construction.

This brings me to my final point on what it takes to be a scholar of rhetoric of identity: reflection and ownership. To be a scholar of anything requires a  dedication to metacognitive reflection, rhetorical identification perhaps moreso because of the uniquely personal nature of identity research. These times of reflection should lead to a sense of ownership that moves one to civic engagement of some capacity. Ivory towers and academic silos are not where English Studies belong, much have we have discussed this semester; and any scholar of rhetoric of identity should show ownership of this move to engage the public with ideas, theories, and findings. Everyone has an innate desire to belong; identification rhetoric can provide a means for engaging this desire to be “both joined together, yet separate from” a community (Burke 1325). For me, in this phase of my life, being a scholar of rhetoric of identity means that I make myself consubstantial with my students, with my academic classmates and colleagues, and with my diverse community groups.

dedication to metacognitive reflection, rhetorical identification perhaps moreso because of the uniquely personal nature of identity research. These times of reflection should lead to a sense of ownership that moves one to civic engagement of some capacity. Ivory towers and academic silos are not where English Studies belong, much have we have discussed this semester; and any scholar of rhetoric of identity should show ownership of this move to engage the public with ideas, theories, and findings. Everyone has an innate desire to belong; identification rhetoric can provide a means for engaging this desire to be “both joined together, yet separate from” a community (Burke 1325). For me, in this phase of my life, being a scholar of rhetoric of identity means that I make myself consubstantial with my students, with my academic classmates and colleagues, and with my diverse community groups.

Works Cited

Althusser, Louis. “From Ideology and State Apparatuses.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 1335-1360.

Bizzell, Patricia, and Bruce Herzberg. “Quintilian.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, 359-364.

Burke, Kenneth. “From A Rhetoric of Motives.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present, edited by Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2001, 1324-1340.

Butler, Judith. “From Gender Trouble.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 2540-2552.

Depew, Kevin. Personal interview. 5 October 2016.

Foucault, Michel. “From The Order of Discourse.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed., edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al., W.W. Norton & Company, 2010, 1460-1470.

Glenn, Cheryl. “Remapping Rhetorical Territory.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 13, no. 2, Spring 1995, pp. 287-303. JSTOR. Sept. 14, 2016.

Katz, S. B. “The ethic of expediency: Classical rhetoric, technology, and the Holocaust.” College English, vol. 54, no. 3, 1992, pp.255-275. JSTOR. Oct. 4, 2008.

Kopelson, Karen. “Dis/Integrating the Gay/Queer Binary: ‘Reconstructed Identity Politics’ for a Performative Pedagogy.” College English, vol. 65, no. 1, pp.17-35, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3250728. Accessed 12 Oct. 2016.

Showalter, Elaine. “Introduction and Chapter 1.” A Literature of their Own: British Women Novelists from Bronte to Lessing. Expanded Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1999. p. xi-36. Print.

from which to pull objects of study.

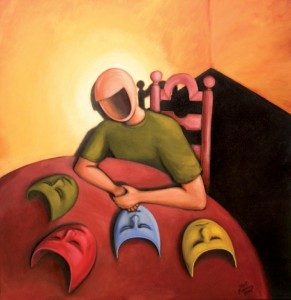

from which to pull objects of study.  intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

intentions behind my research interests in rhetoric of identity: I am largely still trying to figure out my own identity. I don’t entirely know what I want to be when I grow up and there are many layers within my thirty-one years of life that have played a part in who I am as a scholar and truth-seeker, an educator, a student, a wife, a friend, a daughter, etc. Behind each aspect of my identity lies questions of how that construction came to be.

Aristotle’s

Aristotle’s  theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to

theories. It is precisely these “inner voices” that a rhetor needs to tap into in order to rhetorically impact the self-structure. Alcorn also looks to  beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” (

beginning of this movement. Of course the earliest moments of recorded rhetorical history are male-dominated, much like the traditional rhetorical canon. Many of these earliest rhetoricians dedicated their lives to education in the rhetorical tradition. Quintilian is one such rhetor. His infamous mantra of “A good man speaking well” is clear in its underlaid emphasis on the identity construct required of any good rhetorician (Bizzell and Herzberg 359-363). Cicero is another such rhetorician. He speaks to the importance of “integrity and supreme wisdom, and if we bestow fluency of speech on persons devoid of those virtues, we shall not have made orators of them, but shall have put weapons into the hands of madmen” ( conversation, uses the term

conversation, uses the term  so far. For example, Nugent and Ostergaard’s distinction between preservation and transformation is a different aspect of the same conversation. The very nature of English studies is rooted in an ever-changing history with dynamic boundaries that span disciplines from communication and linguistics to the pragmatic sub-fields of composition and pedagogy. McComiskey talks directly about the topic of identification in calling for integration within the field of English studies. Miller discusses the four disciplinary corners that make up the ambiguous field of English studies. Glenn’s discussion falls right in line with these concepts. To point to a static history would be a mistake as undoubtedly, there are still aspects, or angles to borrow Glenn’s terminology, yet veiled to our current modes of inquiry and research methodologies as they are fluid and even undefined in some sub-fields.

so far. For example, Nugent and Ostergaard’s distinction between preservation and transformation is a different aspect of the same conversation. The very nature of English studies is rooted in an ever-changing history with dynamic boundaries that span disciplines from communication and linguistics to the pragmatic sub-fields of composition and pedagogy. McComiskey talks directly about the topic of identification in calling for integration within the field of English studies. Miller discusses the four disciplinary corners that make up the ambiguous field of English studies. Glenn’s discussion falls right in line with these concepts. To point to a static history would be a mistake as undoubtedly, there are still aspects, or angles to borrow Glenn’s terminology, yet veiled to our current modes of inquiry and research methodologies as they are fluid and even undefined in some sub-fields.